A series of posts have been cooking, in part, because of NPR’s Barbara King who occasionally writes on animal rights & hunting. I recommend her columns for those interested in an animal rights perspective.

First, I’d like to address a particular misconception around hunting and the kill. Hunting is just about killing in the same way Burning Man is just about taking mushrooms and having relations with strangers in the desert. Perhaps technically true from a certain perspective and for certain people, but they both miss out on the incredible, transcendent wealth of experience people have outside of that narrow view. And by taking the narrow view you close yourself off to a vibrant culture, understanding, and transformation.

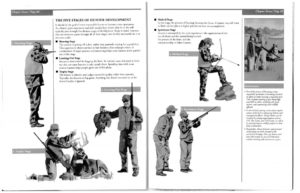

Hunting is actually about reaching a transcendent, all-consuming study of nature. If you take a look in the California Hunter Education manual, there is even a “hierarchy” of hunter development, which I compare to Maslow’s Hierarchy. The highest levels of development place the process of hunting—of simultaneous observation and blending with nature—at the forefront of the hunter’s mind, rather than the focus on the end result, the kill. Many of the older hunters I know swear off firearms altogether in favor of bows, which because of their limited range, generally represent a much greater challenge at integrating yourself into the landscape.

This all-consuming study is fundamentally different than any other kind of wilderness observation. You do not have the same experience bird-watching for example. Hunter Harry Greene, interviewed for a Barbara King column, identifies a “deeply provocative engagement” that he has never found elsewhere, even as a life-long wilderness explorer. What Harry struggles with here is the near-mystical way of being at the confluence of a number of factors which I will attempt to unpack below, to the best of my limited understanding.

- There is a level of alertness and awareness you cultivate that is unlike anything in your daily experience. The amount of information you have to process in parallel to be successful is tremendous. You are taking in information from all your senses at maximum attentiveness. The feeling of the wind direction, any smells that come through. Visually you scan for tracks, food sources, beds, camouflaged shapes. Empathically, you are connecting to the ideal animal and what it is thinking and doing as it walks through the landscape. You must transcend the ~40 bits of information you have access to in your rational consciousness and become simultaneously a part of the environment, and a part of the animal you are hunting. Have you ever been to a place so dark you can see the Milky Way at night and lost yourself in the stars? That is a closely related feeling for me personally.

2. It is often physically and mentally challenging. I prefer backpack hunting, where I go deep into a roadless wilderness with what I can carry for days at a time. That is extreme, but every hunt has its own challenges. Often hunters must contend with extreme cold, extreme heat, physical exhaustion, or simple boredom.

Combining these first two points; bringing a wandering mind back to a central focus despite physical and mental discomfort is the fundamental process of meditation, is it not? Hunting is, at its root, a mindfulness practice, not a killing one. Think of the certainty of days spent in observation versus the possibility of minutes actually taking a shot and killing an animal — it’s no contest as to what constitutes the core experience of hunting.

3. If there is a kill, it is a transformative experience. I guarantee you will not view death in the same way before and after. Tim Ferriss experienced this as a guest on Steven Rinella’s show MeatEater. He says,

“There is a very core part of my being that I had not expressed…and I didn’t realize it until I went on the hunt with Steve. […] It was the weirdest experience. I vowed not to romanticize hunting, but I am now more comfortable with the inevitable cycle of life and death that includes everything around us. Discovering this first hand has led me to feeling more human and also more calm, for reasons I can’t fully explain myself.”

(Season 4, North Slope Alaskan Caribou for the interested)

A dear hunter friend of mine was recently diagnosed with an aggressive cancer. He appeared to come to acceptance of it in record time, even as those around him reacted anxiously.

For my part, I have experienced this calm as well, although it is not been as yet severely tested.

4. Combining the above, I must point out that as a hunter-gatherer species we, in some sense, have deep-seated neurological connections to the hunt. To use our brains for hunting-focused nature observation in the way they came to be tens of thousands of years ago is such a deep-seated feeling that I find it difficult to describe. I am compelled to relate the time I took a road trip cross country with my bookish best friend who never played sports growing up. When stopped at a campground in the high Sierras, I taught him to throw properly for the first time using stones, and he reacted with such simple joy and wild abandon I smile to this day.

There is a special, secret satisfaction for those who reserve for themselves some Stone Age actions.

Why can’t hunting just be nature observation alone then? Why must it have the possibility of a kill at all? It sharpens the senses, fights off the distractions. It primes the brain for the different set of values & uses it will have on the journey, even if the hunter never encounters the animal he is looking for. Finally, it closes the loop on becoming a part of the landscape, taking it into yourself. I’d love to interview Rinella on this topic, given my limited hunting experience.

As a last point, I must point out a last misconception I feel is common among anti-hunters, particularly in these intersectional days. Often, they inadvertently confuse the motivations behind modern-day hunting and the market hunters responsible for past extinction and near-extinction events, like the near extinction of the buffalo or the extirpation of elk in the majority of the country.

By this, I mean they largely see white men projecting themselves into the world rapaciously, without regard for the environment, with the twin madnesses of greed and bloodlust in their hearts. I’d like to remind everyone that modern-day conservation hunting has very little to do with this shadow. It has nothing to do with making a profit, nor, as I hope I have shown, deliberately projecting yourself onto an animal with cruelty in your heart. Modern hunting has everything to do with enjoyment of the experience outlined above, and, as I theorize next, an essential view of the world. Modern hunters are actually responsible for championing and funding many of the programs responsible for reversing the insanity of past market hunters, from Central Valley California wetlands to the Kentucky woodlands again sounding with the bugle of elk.